Text | Conversation | Gropius Bau 2022

Repairing the Social Fabric: Amid the Burden of History

A conversation between Brook Andrew and Marcia Langton

Aboriginal kinship systems can operate as forms of healing from the legacy of colonialism. Artist, curator and scholar Brook Andrew and anthropologist and geographer Marcia Langton explore how – while the fight for recognition of Indigenous peoples in Australia is still ongoing – community-based projects in research and art build non-institutional sites of mourning, remembering, sharing and restituting cultural heritage.

When Australia became a federated country in 1901, Indigenous Australians were entirely excluded from discussions concerning the creation of a new nation to be situated on their ancestral lands. It was not until a referendum in 1967 that two racist clauses were removed from the then adopted constitution. A series of experiments to give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples a say has failed, mostly because of government refusal. Across Australia, pressure continues to build for Indigenous peoples to be part of genuine shared decision-making and to have their voices heard by the Australian parliament and government in policy and law drafting. The extract below is an edited talk between artist, curator and scholar Brook Andrew and anthropologist and geographer Marcia Langton on how to meaningfully recognise Indigenous Australians, which took place during Ámà: 4 Days on Caring, Repairing and Healing at the Gropius Bau in 2021.

[Content warning: Colonial violence, racism]

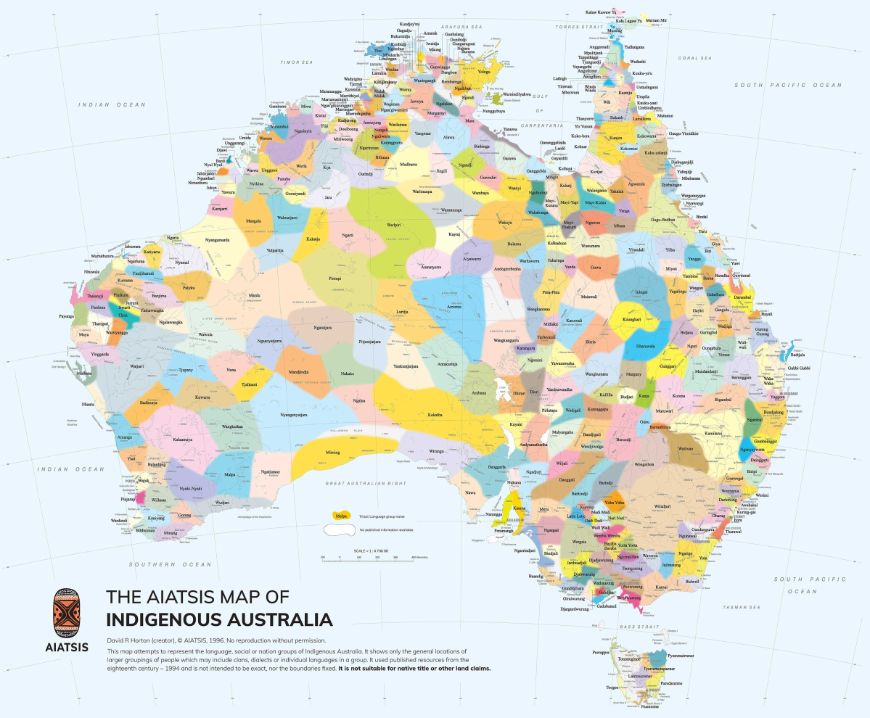

AIATSIS map. This map attempts to represent the language, social or nation groups of Aboriginal Australia. It shows only the general locations of larger groupings of people which may include clans, dialects or individual languages in a group. It used published resources from the eighteenth century-1994 and is not intended to be exact, nor the boundaries fixed. It is not suitable for native title or other land claims. David R Horton (creator), © AIATSIS, 1996. No reproduction without permission.

Brook Andrew: We’ll be talking about kinship, caring, repairing, healing, and will focus on the Western Desert as an example to look at some of the kinship connections there. This map of Australia depicts over 300 different local nations and languages and it’s really important to speak about their sovereignty.

Marcia Langton: Amongst those of us that work in this area, this map is referred to as the “Horton Map” (1) as it was devised by the Australian writer David Robert Horton. There’s usually a warning to say that it should not be relied on in native charter claims, but it’s useful for any audience in explaining the great diversity of Aboriginal Australians – the descendants of people that came here more than 65.000 years ago – and Torres Strait Islanders, who have lived in the region for about 20.000 years.

Australia was colonised around 250 years ago by the British, and in the late 19th century, white colonists in the six separate colonies decided to unify them as a nation. The Australian Constitution was drafted based on the principle of a country for the white man at a series of conventions that excluded Aboriginal people entirely. There were several racist clauses in the constitution: two of them were removed at a referendum in 1967. However, it didn’t solve the problem as the constitution remains formally racist: the “races power” in the constitution, for instance, gives the parliament the power to make laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and it can do so to their detriment.

Andrew: The very first Indigenous Minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt, has recently unveiled plans to work towards establishing advisory bodies, or “voices”, to consult local state and territory governments on policy decisions that affect First Nations people. You’ve been working with the Indigenous social justice activist and scholar Tom Calma on a report of the so called “Indigenous Voice” over the past years. Could you tell a bit about the project and the conversations around recognition within the constitution?

Langton: In late 2019, Minister Ken Wyatt appointed 52 of us to co-design an Indigenous voice to parliament. This came about because of the Uluru Statement from the Heart which resulted from the first National Indigenous Constitutional Convention (2017) at Uluru in Central Australia. 250 Aboriginal delegates attended this meeting and wrote the statement, addressed to all Australians calling for a voice; a treaty commission called Makarrata (2) and truth-telling. Our voice co-design process was strongly influenced by that statement and other developments, leading to a final report which has been submitted to the minister in July 2021. It presents how Indigenous people might have their voice heard in the parliament and we’re currently waiting for the cabinet to consider it.

In three jurisdictions now, we have treaty processes: the most advanced one is in Victoria, where there’s legislation and a treaty commission called the First Peoples’Assembly of Victoria. There’s also a treaty process commenced in Queensland and a quite advanced process in the Northern Territory where there’s a treaty commissioner and assistant commissioners. In Victoria, an act has also been passed establishing the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission (3), which has the power of a royal commission: to investigate matters that fall under the rubric of truth-telling about the historical past in relation to what happened to Aboriginal people.

Colonial Frontier Massacres. Australia, 1780–1930, Screenshot. Courtesy: Frontier Massacres

Australia had a very violent colonisation – extremely violent. There is a major research project called Frontier Massacres mapping all the documented massacres across Australia online. The researchers are progressively working their way from the East to the West coast of Australia and there are hundreds of sites. Each dot on the map represents such a place and there are supporting historical documents that summarise body counts, details of what happened, dates and so on.

This backdrop of a brutal colonisation and the denial of our civil rights – constitutionally and legally – needs to be understood as part of the picture when we talk about kinship. As you can imagine, not many of those kinship systems have survived intact. A large part of our population is now urbanised or living in rural towns and has been denied, for many years, the right to speak our own languages. With the loss of language, you also lose cultural detail, like kinship terminologies and all that goes with it. But there are resonances of the ancient kinship traditions amongst most Aboriginal people, and we still practise those traditions of recognising each other as kin. So, even though we both have no biological relationship, we still class each other as family because of this ancient tradition of adopting each other as kin folk.

Andrew: I think it’s important to note here, too, that in our traditional lands, the pain that we still feel – the intergenerational trauma – really needs a lot of murumgidyal, which is “healing” in Wiradjuri (3). For us it’s an ongoing healing process, not only on a constitutional level in being recognised in our own country, but it is also a continuous healing that we’re always having to perform.

Langton: From an Aboriginal perspective, kinship links us all and to the world around us. It’s not like English kinship terminology that only gives us terms for mother, father, brother, sister etc. Aboriginal kinship encompasses a great deal more – it’s a kind of social logic. All those surviving, intact kinship systems must be very ancient. They explain the world in relation to all known human and non-human phenomena, creating a network of relatedness which we inherit. In them, not only people and their familial relationships are classified and named, but also many other people, so that all become related. We establish a kinship connection and kinship names we will call each other, and if we can’t establish a biological connection, we create one. Potentially everybody is related to each other, in other words. These systems include all named living things, features of our environments, celestial bodies and (sacred) ancestors, as well as the places, land and sea estates.

In that sense, ancestors are not forgotten, and the massacres create a double burden. Not only do we know that many of our people were killed – in each family, we have stories of that, or we might learn about them as adults in a library, as records come to light – but we also have these great absences in our social life, because so many people were murdered or died from disease during the colonial invasion. It’s very difficult for people to create firm linkages back to their ancestral places which is why we spend a great deal of our time on doing research and talking to each other; interviewing kinfolk to ensure that we have the best possible chance of re-establishing those relationships with the past. For instance, my daughter went up to a big tribal get-together recently for a native title determination, and we have hoped to go to Queensland to visit a sacred stone – The Star of Taroom – which was returned to the country. These gatherings are tremendously important as modern-day ceremonies and markers that bring people together again.

Andrew: Evidence of massacres have long been deliberately hidden and made invisible. The denial of these and other actions have been and still continue today. In regard to the digital massacre map on the frontier wars, I myself found a private letter sent from Former Premier of Queensland, James Robert Dickson (1832–1901), from the Snowy Mountains region of Victoria, back to his friend in England in 1854. In it, he described a massacre, where 17 Aboriginal people were murdered. I forwarded this on to that project and so it’s really through these means and other research that we form historical spaces that also help with kinship and healing.

From an Aboriginal perspective, kinship links us all and to the world around us.

— Marcia Langton

Langton: There’s more and more research on what is called “the impact of intergenerational trauma” caused by these massacres which leads to mental and physical ill health. So, when people talk about healing and truth-telling, it is a nationwide challenge to find ways to overcome the legacy of colonial invasion; to make people, families and genealogies whole, and to do our best to restitute our cultural heritage. These are all acts of healing.

Andrew: There are also examples of healing processes initiated through kinship relationships in art projects, for example in the Great Western Desert.

Langton: Yes, in 1996, 40 claimants were making a native title claim through art. They gathered in Lake Pirnini in the Great Western Desert to demonstrate their claim to land which resulted in a five by ten metre canvas called Ngurrara, which is now in the collection of the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. One year later, the makers involved even more people, creating a kinship network across the Western Desert and bringing in more claimants to land to create a second 80 m2 large iteration of Ngurrara. It depicts a vast landscape with its sacred waterholes (jila) and soaks (juma) across the desert and there’s a line that represents The Canning Stock Route, an 1850-kilometre-long track running between Halls Creek and Wiluna in Western Australia. It is named after Alfred Wernam Canning who surveyed the route in 1906–07. The native title claim was finally heard in 1997 and the native title tribunal members travelled to Lake Pirnini. Each artist stood on the section they painted and spoke about their connection to country in their own language which became a crucial evidence in their claim for native title. It took another ten years, however, before it was officially recognised.

In 2017, this second painting was returned to the people in the Great Western Desert and the new generations – after 20 years – came together for a ceremonial gathering that had the purpose of awakening the painting. This is a great example of how people are using their kinship and ancestral connections as well as their cultural toolkits to heal and restitute their social lives and their societies.

Marcia Langton is a descendant of the Yiman people of Queensland and holds the Foundation Chair of Australian Indigenous Studies at the University of Melbourne. She has produced a large body of knowledge in the areas of political and legal anthropology, and Aboriginal arts and culture.

Brook Andrew is an Australian Wiradjuri artist, curator and scholar. His practice imagines alternative futures and challenges limitations imposed by ongoing colonial actions to re-centre Indigenous ways of being. He is co-curator of a group show on caring, repairing and healing which will be presented at the Gropius Bau in 2022.

Endnotes1 The official name of the maps is: “ AIATSIS Map of Indigenous Australia”, (accessed 24 February 2022).

2 Makarrata is a word in the Yolngu language meaning a coming together after a struggle, facing the facts of wrongs and living again in peace.

3 Yoo-rrook means “truth” or “truth-telling” in the Wemba Wemba/Wamba Wamba language

4 Wiradjuri is an Australian First People (Aboriginal) Nation and language is a Pama–Nyungan language of the Wiradhuric subgroup located in western New South Wales, Australia.