Text | Essay | Gropius Bau 2022

The Rise of an Indigenous Europe and the Genealogies of Indigeneities

By Elizabeth A. Povinelli

An end to this world: Elizabeth A. Povinelli traces her own family’s migrations alongside the ancestral displacements that led to the formation of Karrabing, as a way of re-imagining Europe and its diaspora through the lens of decolonisation.

With ear-shattering rhetoric and low-frequency suggestions, the far right and progressive left have made moves toward reimagining an Indigenous Europe. However the social and political intentions and goals across these movements could not be more divergent. Take, for example, the egregious anti-immigration campaign of Italy’s political party Lega Nord per l'Indipendenza della Padania, which advocates greater regional autonomy and fiscal federalism and has crudely associated the experiences of Native Americans with peoples in the regions of northern and north-central Italy.

Lega Nord polls just over a quarter of the vote in provincial elections in the province of Trentino, the autonomous region that includes my paternal village, Carisolo. The current President of Trentino, Maurizio Fugatti, is the head of Lega Nord Trentino and garnered nearly 47 percent of the vote. Lega Nord’s claim to have suffered a history similar to that of the Native Americans’ land dispossession began as early as 2012, when the party’s supporters appropriated the imagery of the Great Plains warrior – face paint, eagle feathered headdress, bone necklaces. In Milan, journalist Saverio Tommasi reports as “alla scoperta dell’ultima tribu” (“discovering the last tribe”). Posters soon followed, with an image of a Native American warrior warning, “Loro non hanno potuto mettere regole all’immigrazione. Ora vivono nelle riserve!” (“They were unable to set immigration rules. Now they live on reservations!”).

In a counter movement, progressives are excavating local and regional pre-Christian and pre-capitalist modes of rapport with the more-than-human world. They reject the white supremacist possessive logics of enlightenment humanism as the culmination of a history of violent colonial and imperial accumulation. They are allergic to the cultural appropriations that are so viscerally visible in the fascist gestures of far-right groups such as Lega Nord, and to the resignifications of early-European symbols such as the Celtic cross. The purpose of peeling back these histories is to write a different history of the present, one that would support an anti- and decolonizing alliance with First Nation/Indigenous peoples globally.

These divergent movements intimately crisscross my personal history. My natal family was raised under the affective and discursive domination of my paternal grandparents, who both came from a small village in Trentino. They were members of two autochthonous lineages of the village, Povinelli and Ambrosi – six lineages in total are recognised. My grandfather was a member of one of the earliest clans (termed scotuma) of the Povinellis – the Simonatz Povinellis. When I was two and a half we moved from Buffalo, New York to northern Louisiana, the homelands of the Caddo people, who in the 1860s had been forced into Oklahoma. The colonial and racial violences that marked the history of northern Louisiana sat silently in the background as my grandparents’ raged about their own violent dispossession. Blurred accounts came via languages that I could not understand: not merely Italian, but the dialect spoken in Carisolo, which linguists call Ladin.

Their personal grievances of loss and injustice had deeper histories. A local customary law that allowed the autochthonous families to determine the sharing of their communal lands and resources was overthrown, first by a Bavarian invasion, then Napoleonic, the Hapsburgian and, ultimately, the Italian. So too were intimate relations with the more-than-human world – especially with the cows that were bred for glacial heights, and with whom families sometimes slept for warmth, but also the streams of fish, the chestnuts and mushrooms. Amid frontier violence, poverty and the dispossession of local ways of possessing each other, the more-than-human world was the affective and discursive soil in which I emerged side-by-side American practices of the same. This history was relatively shallow when I entered it. My great grandparents left Italy in the 1890s for Buffalo, New York, where they began Povinelli Knives on the lands of the Seneca people. Other Simonatz went to Australia. By end of 20th Century, no Simonatz Povinellis were left in our village.

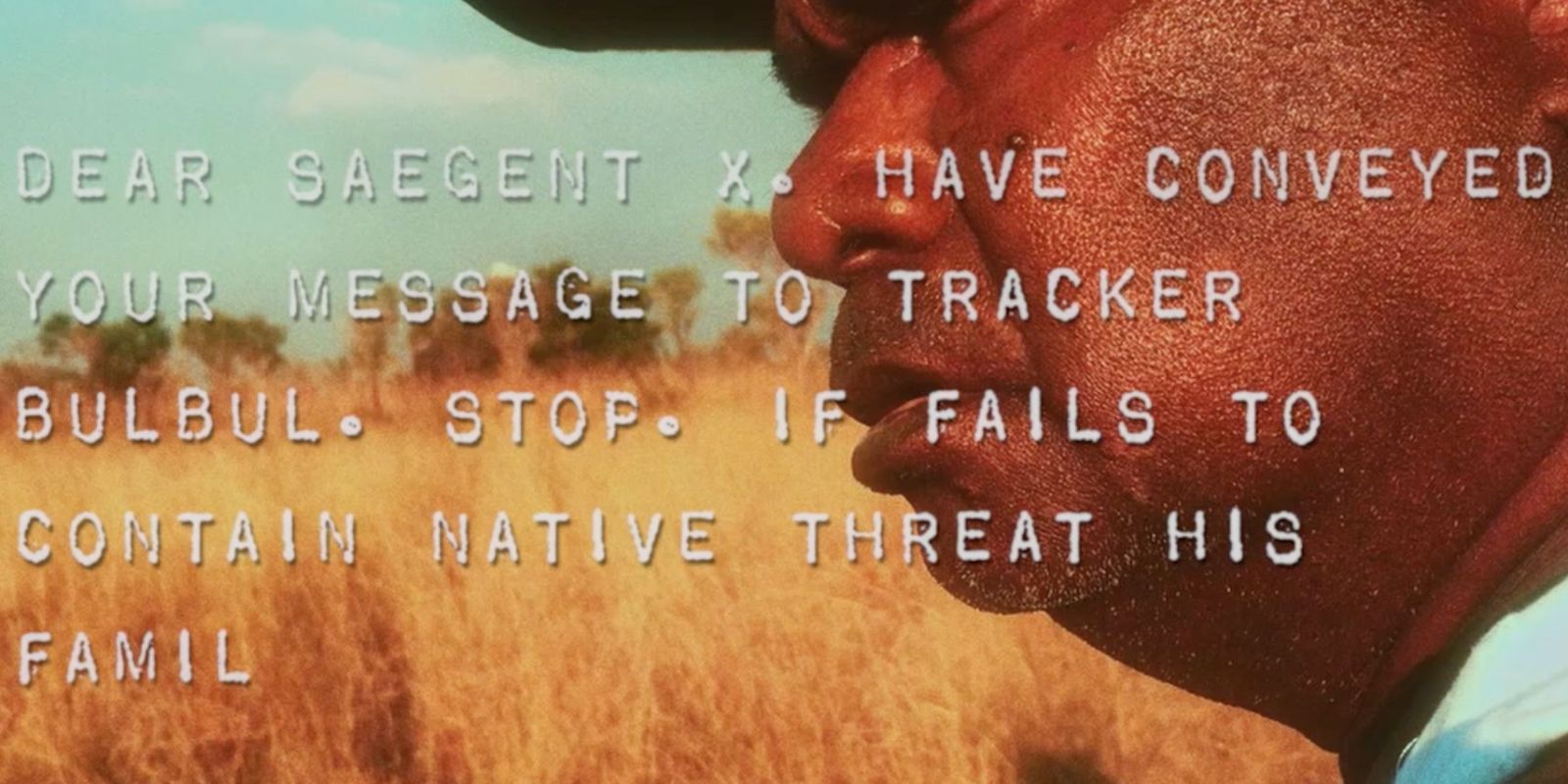

The northern shores of the Australian continent also have a relatively shallow history of settler frontier violence. The city of Port Darwin began in 1869 just over 75 years after the invasion of Gadigal lands – which today is known as Sydney. Kadapurr and Koinmurrerri, ancestors of those who form the core of Karrabing, were born around the same time as my great grandparents, Giovanni and Candida. They bore five sons and two daughters in the early-1900s. These men and women remained in their homelands, moving north and south along the coast until the late-1930s, when they were forcibly interned at Delissaville on the Cox Peninsula just across the Darwin Harbour as part of a colonial state tactic of containing and eliminating Indigenous worlds. Delissaville settlement was evacuated because of the Japanese attacks on Darwin and moved to a new internment camp at Katherine in the Northern Territory. Kadapurr and Koinmurrerri’s sons, George Ahmat and Benggwin Wanggagi, escaped with their wives and children, returning to their homelands until after the end of World War II. They were subsequently forced to return to Delissaville. Alongside the other senior men and women, they articulated new forms of social and ceremonial belonging through a network of underground totemic tunnels and ancestral beings,(1) which refused the settler logics of property and possession. As settlers sought to fence Indigenous people’s relations to land, Indigenous men and women used their relations to the more-than-human world to extend their agency.(2)

I arrived at Belyuen – the name given to Delissaville by its Indigenous community – some eight years after the passage of the federal Land Rights Act (Northern Territory) 1976 (LRA). The stated intention of the LRA was to provide Indigenous people in the north a means for materially grounding an autonomous self-determining society. Ruby Yarrowin, the last paternal descendent of Kadapurr and Koinmurrerri, had just lost her husband, Roy Yarrowin, who was a ceremonial and political spokesperson for the community. Belyuen was in the midst of a land claim that would last until 1995. As the land claim wore on it became clear that state recognition of Indigenous self-determination was based on a devious approach. It sought to transform the local rapport between human and more-than-human worlds into what academic Aileen Moreton-Robinson has called the logics of the white possessive – a mode of relating to all existence from a European viewpoint, which is predicated on the superiority of humans over all of creation. Novelist and philosopher Sylvia Wynter would come to call this the “overdetermination” and “overrepresentation” of the human from the perspective of western modes of humanism.(3)

The descendants of Kadapurr and Koinmurrerri define the core of the indigenous media group Karrabing Film Collective – of which I am a member. The Karrabing Film Collective emerged in the early- to mid-2000s after the stated intention of the LRA had long given way to the true mechanizations hidden within it. Individual Indigenous lands and clans were sealed off from each other, imaginary and real fences raised, in order for the state and capital to address Indigenous worlds using proprietary language and terms. The logics of property inserted into the era of so-called state-authored self-determination ignited endless rounds of intra-Indigenous antagonisms. As the senior Emmiyengal Mudi (which is short for Barramundi Fish) Karrabing member Rex Edmunds has observed, as part of land rights-based legislation, whether intended or not, Indigenous people were set against each other rather than government and the businesses that sought to exploit their lands. Karrabing seeks to hold in place a different relationality, one summarized in the creole phrase, “roanroan and connected”, which essentially means “One’s own because of its connection to others”.

In a series of short manifestos made for the digital exhibition Medium Earth (2020) at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Karrabing members Rex Edmunds, Cecilia Lewis and Natasha Bigfoot Lewis emphasise the coterminous and interdigitated relationship among the multiplicity of languages, lands and stories. These characterise the family (totemic) groups within the Karrabing Film Collective, while holding firm to the interconnecting stories, ecologies and social relations that hold them together in their difference.(4)

By 2017, Karrabing had begun travelling to Europe for shows that featured our work. During the Contour Biennale 8, Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium, curated by Natasha Ginwala and held in the city of Mechelen, Belgium, three members of Karrabing travelled to the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, Netherlands to also discuss the possibility of showing our work there. While the curators Vivian Ziherl and Annie Fletcher walked us through an exhibition, Rex stopped, absorbed by a series of prints that depicted the slaughter of Catholics by Christians. The imagery of disembowelment was strikingly similar to the traditional mode of butchering kangaroos – the hanging by a leg, the removal of the viscera, the sorting of organs into different piles. Rex asked me whether this had really happened, reading it as a prehistory of his own ancestors’ treatment. “So they slaughtered their own like kangaroo, and then came did the same to my ancestors”, he said.

Two years later, Rex Sing, Linda Yarrowin, Aiden Sing and I made a quick trip to Italy, aiming to visit Carisolo after an event in Paris. We met with a local genealogist, Edna Nella, who wanted to go through my Simonatz scotuma family history with me. As Rex, Linda and Aiden looked on, we travelled back through time to the early-1700s, tracing each branch through the paternal line. Afterwards, Linda and Rex laughed, saying that they now believed my family had clans but wondering whether this mob has dreamings (totems) too. I said, “who knows, maybe once.” Today we have old stories of elves and witches. But it could be that, just as some settlers try to do Karrabing ancestral beings and spirits, whatever existed and still exists now has to emerge through a Christian storyline.(5)

Why tell these two stories? They lay at the heart of the stakes of reimagining an indigenous European history – genealogically rather than comparatively – within a decolonizing practice, as opposed to a framework of disavowal. This difference is, I believe, crucial if our project is, as Denise Ferreira da Silva has proposed, an end of this world in order to make way for another: to see Europe and its diaspora turn away from one history to reclaim the possible futures of another.(6)

Three points are crucial on the left:

First, that one is from a history of frontier violence. Dispossession does not mitigate the differential powers and effects of moving across such frontiers. My Simonatz ancestors experienced and passed down the effects of violent dispossession of their rapport with others and their lands. Nonetheless, they possessed the ability to take advantage of a history of colonialism and racism, not merely to settle onto the lands of the Seneca and the Caddo without acknowledging their authority over them.

Second, in general – and as an example – my family benefited from the accumulations of wealth that lay at the root of the United States. We may have arrived fairly late in the country’s history, and we may have suffered from the virulent wave of anti-Italian nativism that characterised the early-20th century and the anti-Catholicism in the KKK-dominated South. Nonetheless, we were white enough. We were quickly absorbed into whiteness as formal and informal Republican-led political discourse consolidated an anti-black practice into the heart of both Democratic and Republican Parties. The barely hidden racist rhetoric of Ronald Reagan’s welfare queen and George H.W. Bush’s Willie Horton advertisements went side-by-side with Bill Clinton’s destruction of the federal social safety net.

Third, the travel through these histories and their differential effects cannot be occluded by abstracting out aspects of correspondence. When I first met the parents and grandparents of the Karrabing, we were all struck by the deep overlaps of my ancestral relation to Carisolo, as well as theirs to Naddidi, Tjindi, Nganthawudi, Mabaluk, Banagaiya, Banagula, Bwudjut and Belyuen. But by the time we met, the effects of our differential treatment were equally clear.

As for the right, when Lega Nord pastes their placards of Native American futures, they refuse not only the fictions of origin but the facts of the origins of northern Italian and European wealth – the colonial and imperial accumulations as an effect of the swallowing up of other worlds. A Native American world should be their future. Yet this world would take back every ear of corn that made our north Italian polenta, leaving the north as it was when my ancestors left: a poor frontier on the outskirts of everywhere. If someone is coming for what you have, it is because you took it from them.

Elizabeth A. Povinelli is a critical theorist and filmmaker. Her critical writing has focused on developing a critical theory of late settler liberalism that would support an anthropology of the otherwise. This potential theory has unfolded across five books, numerous essays, and a thirty-five years of collaboration with her Indigenous colleagues in north Australia including, most recently, six films they have created as members of the Karrabing Film Collective.

Endnotes

1. For a deeper discussion of the ways in which these Indigenous men and women used their ancestral logics to transform dispossession into belonging see “The Poetics of Ghosts” in Elizabeth Povinelli, The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 187-284.

2. See Karrabing Film Collective, The Jealous One (2017) and Night Time Go (2017). See also Elizabeth Povinelli, Cunning of Recognition (see Note 1).

3. See Ailene Moreton-Robinson, The White Possessive: Property, Power and Indigenous Sovereignty (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015); Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation – An Argument”, CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003), 257-337.

4. For a discussion of the political imaginary of the artistic practices of Karrabing, see “Roan roan and connected, that’s how we make Karrabing.” Medium Earth, Art Gallery of New South Wales. https://togetherinart.org/karrabing-in-medium-earth/ . See also Elizabeth Povinelli, The Inheritance (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021) – forthcoming publication.

5. Zoe Todd, “Fish, Kin and Hope: Tending to Water Violations in amiskwaciwâskahikan and Treaty Six Territory”, Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 43 (2017), 102-7.

6. Denise Ferreira da Silva, Toward a Global Idea of Race (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).