Text | Essay | Gropius Bau 2022

Planetary Portals: “Dreaming in Continents” from East London to the Cape in the Colonial Praxis of Emergence and Extraction

By Kathryn Yusoff, Kerry Holden and Casper Laing Ebbensgaard

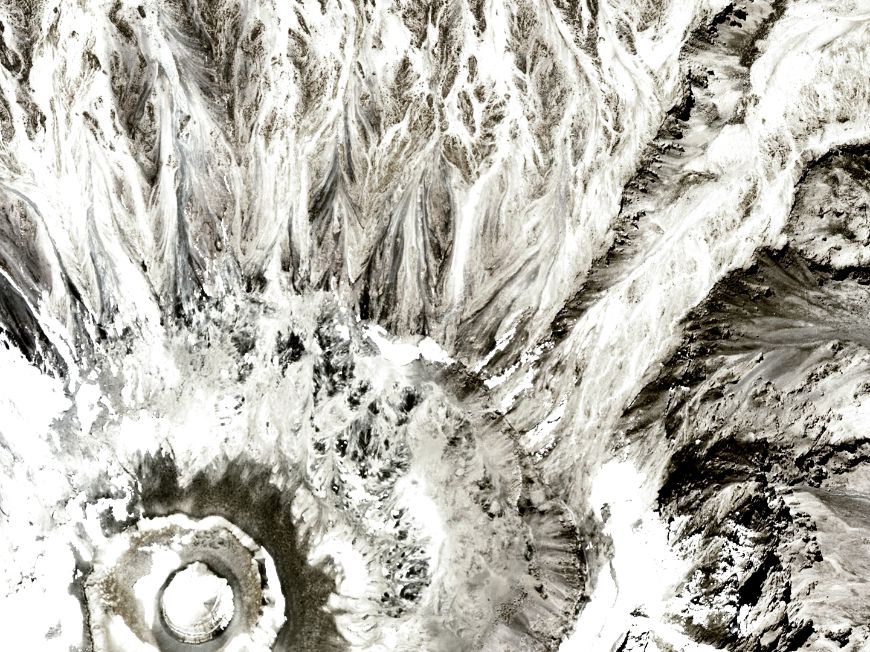

The European imagination shaped a vision of other continents as resource, ripe for ongoing extraction – creating processes that continue today. Based on original research in the Rhodes archive, this collaborative work examines the emergence of “planetary portals”, and considers how they might be decolonised.

Featuring original artworks by Michael Salu.You need to enable Third party cookies to view this content.

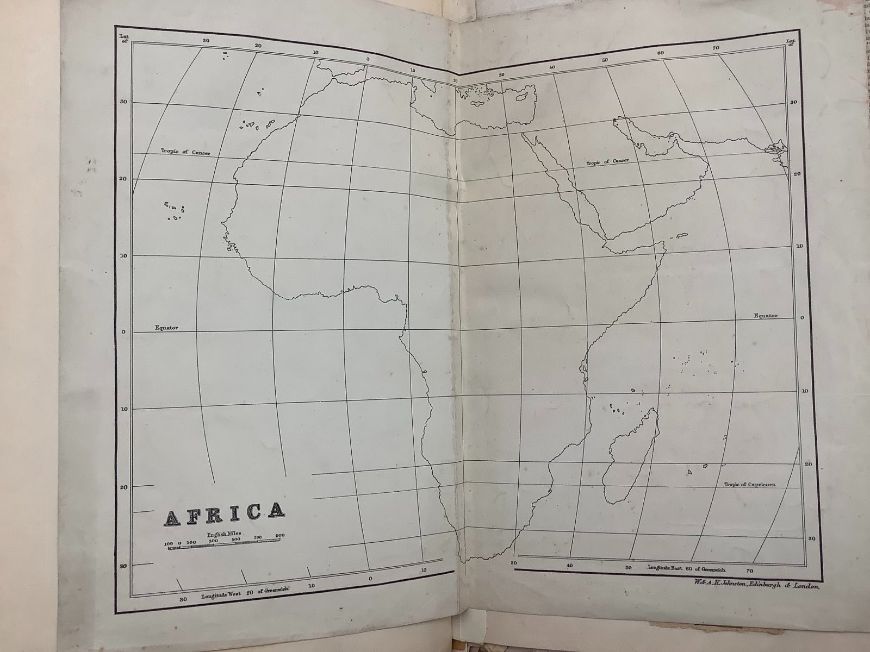

The invention of Africa through the lens of extraction ties together a spatial imaginary, dreamed from the slum housing of the Rhodes estates in Dalston, East London, to the Cape of South Africa. These speculative imaginings drew an empty continent, bifurcated by railway line and telegram, to encapsulate the view northwards–copper and steel extending from Cape to Cairo. Through this portalled perspectivism the continent of Africa emerged as a colonial fantasy “dreamed in continents”, whereby colonial architectures hold open Africa as a continent for extraction. The portal that opened in Dalston was a spatial expander, from the “development” of multiple occupancy housing on a farm plot in East London to the homogenisation of a continent under the dream of white supremacy. Cecil John Rhodes (1853–1902) accumulated excessive wealth from his exploits in South Africa; wealth that seeded another dream alongside his continental imaginary of a world organised by the monoculture of language (English), extraction and a racial rubric of empire. Africa became – through the empire-building of England, Germany and other European powers – the last white dreamer continent in the context of rapidly-expanding forms of localised heterogeneity that challenged the global myth of empire.

The dream of a portal to expand time and space, imagined at a continental scale, interned Africa as a silhouetted spatial unit to be sucked into the vortex of racial debt relations and the dynamic architectures of extraction. The wide-angle dreaming in planetary portals exhibit a suck of temporal durations into structures of colonial time, with its emancipatory promises of transformation, from speculative finance to material infrastructures. The Jamaican theorist Sylvia Wynter calls this a “material redemption narrative“ (1). Or, the neocolonial model of development by dispossession. The process of portalling through speculation and the extension of physical and bureaucratic infrastructures was an engineering spectacle, a satisfying technological sublime, that continually made Africa as a continent as it unmade it through this relation. This constant emergence of Africa as a continent defined by extraction organises a dual process of surfacing and depletion, promise and terror, that remains in the claims of technological corporations (“Google Africa”), the development-philanthropic complex, and the dark dreams of new empires. Inverting Marx’s maxim that all that is solid melts into air, we seek to show how all that is air (speculation, spatial imaginaries and “dreams” of homogenisation) liquifies all that is solid, transforming one world into another through dreams of promissory capital leveraged on racialised debt and displacement.

In a newspaper article on the Rhodes Family and “Their London Estates” it was said that while the pleasant hamlet near Hackney was transformed from the ground up by brickmaking, Rhodes “dreamed in continents”, using the wealth generated from slum housing in East London to accumulate the capital needed to extend his operations in the diamond fields of Kimberley, South Africa. Switching bricks for diamonds, the portal speaks to a change of state, transforming that which passes through it as an expansionary spatial technique leveraged on speculative accumulation. Thus, the portal constructs and organises materiality, giving it spatial and temporal coordinates that script matter as pluripotent while inscribing its value according to a model of racial deficit. The portal is a way to see imperial imaginings as not a projection over space but a transformation of its temporal-material dimensions. The portal is a spatialising device, that enables the transformation of matter, changing states of matter and making states of political, economic and ecological change. Africa was seen by Rhodes as “the last place” to dream a white empire as a planetary possession, a racial portal to salve the antagonism of revolt elsewhere. Africa became the dream of reunification of a white supremacist colonial earth. A redemption narrative for the reunification with America, Australia etc. into a geologic white supercontinent.

You need to enable Third party cookies to view this content.

Dreaming in continents: from bricks to diamonds

Cecil John Rhodes is remembered, often fondly, as a dreamer. Not just any kind of dreamer, for “he dreamed in continents”. His dreams of continental world-building were forged on the back of the nightmares of those whose worlds he shattered: world-building-through-world-shattering (2). The dream was the racial debt of extractive materiality that elevated the plateaus of whiteness–plunder. According to Reginald Fenton, Director at Kimberly Central,

“all his actions, good, bad, and indifferent, were rooted in one grand conception: namely, the Federal Democratization of the four great English-speaking divisions of the British Empire, beginning with a united or rather “amalgamated” South Africa and with their union with the United States of America (...) as well as possibly the then Socialized Teutonic Commonwealth:– for Rhodes in his ideals was not far short of being a Marxian.” (3)

Rhodes’ dream was to bend the world into four white, English-speaking continents (a tectonic-Teutonic vision of a white supremacy supercontinent) that would form the global empire defined by the geographical transcendence of Anglo-Saxons. The amalgamation of the supercontinent that he dreamed was propelled by the fantasy of homogeneity over the Black earth. His legacy was not the legacy of familial genealogy (Why have children when you can have a country? And why settle for a country when you can have an entire continent?) but that of social reproduction geo-engineered through portal infrastructures. Reproducing infrastructures was a means to the social reproduction of whiteness.

Rhodes, alongside the German Alfred Beit (1853–1906), foresaw that the four diamond pipes at Kimberley were deep and plentiful, which created two problems of technical difficulty and financial instability (4). The deeper the mines went, the more technically complex the extractive process, going beyond the capabilities of most small claimholders. The continuation of rampant unchecked mining of an apparent abundance of diamonds meant that the market value fluctuated wildly, and the black market thrived. Consolidation was the panacea to stabilise the market and maximise the output, which Rhodes and Beit aggressively sought, separately at first and later as figureheads of De Beers Consolidated Mines that is still in existence today (as testament to their monopolistic structures). (5) The road to consolidation required political work, lobbying for changes in the law to combine ownership claims of the existing mines, and entrepreneurial speculation in attracting the financial backing of Anglo-German investors to fund transportation and construction costs of the extensive socio-technical infrastructures required to drill deeper and extract more easily.

Dreaming across continents constituted the affective architecture that made the notorious Diamond Empire a reality as dreams floated on the London stock market, buoyed by slum-lord rents in East London, at the same time as it marked people and places in Africa with a deadly precision. The diamond rush was an event in the organisation of mining labour that left an indelible scar upon Kimberley society. Cornish and Australian miners arrived at Kimberley with expertise in cracking rock, jewellers travelled from Paris, Antwerp and Hamburg – the major European trade centres – to cut, measure and validate the stones, and investors arrived to prospect claims and venture capital. The congregation of multiple parties at the crust of the mine pushed Black men further down into the earth and Black women into the sexual economy of whiteness. A ramshackle town emerged around Kimberley that the English novelist Anthony Trollope (1815–1882) described in 1878 as representing the “apocalyptic architectures” of an upside down world. (6) A world inverted along the colour line. Throughout the 1870s, white miners formed guilds that restricted membership and persistently campaigned to deny claim ownership to those identified as “native”, and in 1894, while serving as Prime Minister of the Cape, Rhodes introduced the “Glen Grey Act” that paved the way to Apartheid by ruling that “native” labourers must carry a pass signed by employers that permitted them to work (7). This act registers as one of the key pieces of segregation law that rendered predominantly Black South Africans a migratory labour force, unable to claim ownership to the means of production and thus forced to leave family and community to find work laying the tracks for the advancing colonial enterprise of the British South African Company – the commercial front to Rhodes’ chimeric empire.

The flow of diamonds from the Kimberley pipes provided Rhodes with the financial and political muscle to veer his gaze north and annex Mashonaland and Matabeleland (which would be renamed Rhodesia and later form part of contemporary Zimbabwe and Zambia) as key agricultural resources along the imagined red-line that stretched from Cape to Cairo. The bloody slicing of the continent in half is symbolic of the genocide committed against Indigenous communities that Rhodes sanctioned in order to squash resistance, and the terror and violence that has since ensued over the course of a century as a result of annexation. Inspired by settler colonialism in North America and the feats of infrastructural geo-engineering that appeared to bend the land to the will of men [sic], Rhodes wanted to turn Africa into his agglomerated state. He was, in the words of Colson Whitehead, seemingly possessed by “the true Great Spirit, the divine thread connecting all human endeavour – if you can keep it, it is yours. Your property, slave or continent. The American imperative.” (8). Or, the psychosis of whiteness achieved through the geographies and genealogies of geology.

Psychosis of materiality and portals of decolonial desire

Scaling up the process and practices of turning the world upside down (from earth into capital, bricks into speculative real estate empires) was refined in Hackney and portalled to South Africa. The laying down of physical infrastructures facilitated a practice of opening portals, into space, into labour, the materiality of finance, mining, racialised labor, bureaucracies, railways and communications that gave the illusion of architectures of transformation through a latticework of extractive practices. While the statues of imperialists fall, the infrastructures remain, forming imperial debris that actively shapes the world today. (9) As a planetary architect, Rhodes was instrumental in constructing the material flows of extraction and violence. His desire to “dream in continents” flung the African continent into a vortex of violence that has been sustained through the racialised debt burdens that “place” Africa in the world. The portal is a disruptive method that pinches, pulls and rips at the idea of the “planetary” as an event surface and sets the conditions for imagining the uneven states of what Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has called “planetarity”. (10)

What does it mean to decolonise the portal? To shred its processes of unequal exchanges and temporal inversion? Rhodes’ dreaming of the continent organised African affectual infrastructures as governed by the psychosis of materiality that anchors the dream and its speculative geographies of continental transformation – a dreamlike image of modernity through extraction – to an on-going psychosis of violence that invests in the dream as the spectre that polices the extraction. The portal establishes a relation that is geographically and historically specific yet able to reproduce in space and time as a definitive architecture of extraction. It establishes an ideal “type” of exploitation – law, extraction, bureaucracy and communication forms obliterate diverse forms of pre-existing time and space and institute relations of power attached to the colonial centre; normalising extraction without accountability. The architectures of stabilisation in geographies of accumulation and depletion (diamonds in SA introduce the problem of abundance and how to create scarcity through monopoly).

Decolonisation is a process of taking the portal apart –destabilising the points of stabilisation, disrupting the legacies of time and space that hold towards the suck effect of portal extraction. Today, Google Africa is replanting the slave route from Europe to South Africa, calling its new private subsea cable after the writer and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano (c.1745–1797). And thus, Equiano is tethered to the geography of his enslavement rather than his subsequent liberatory geographies of the sea. In this naming, he is interned once again in the abyssal depths of the Middle Passage, re-anchoring to this projection of an undersea grave to “open up” Africa to google cloud infrastructures. We might imagine the Black mythos of Detroit techno duo Drexciya here, as an army of aquatic people rise from the subterranean depths to give dignity and another geography of world-building to Black life. The portal as a planetary analytic, that is mobile and migratory, offers a way for interdisciplinary practitioners to map the interconnected geographies and afterlives of colonial infrastructures; constituting spatial imaginaries that were deployed as blueprints in the emergence and maintenance of extractive planetary futures.

Kathryn Yusoff is a professor of Human Geography at Queen Mary University of London. Her research focuses on geophilosophy, political aesthetics and the Anthropocene. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None was published by University of Minnesota Press in 2019. Currently, she is finishing a book on “Geologic Life” and is co-editor (with Nigel Clark) of a special issue on “Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene” in the journal Theory, Culture and Society.

Kerry Holden is a senior lecturer in Human Geography at Queen Mary University of London. Her research centres upon geographical and anthropological approaches to science and technology.

Casper Laing Ebbensgaard is a cultural geographer and lecturer in Human Geography at University of East Anglia, Norwich. His research explores the aesthetic and affective politics of architecture, urban design and urban planning practice.

Archival photographs produced by the Crown Corporation of Cecil Rhodes’ statue on roundabout in Salisbury, 1960. Courtesy: Archive of Rhodesia & Nyasaland, National Archives, Kew

Endnotes

1 Sylvia Wynter, “Is ‘Development’ a Purely Empirical Concept or Also Teleological? A Perspective from 'We-the-Underdeveloped’”, 1996, in: The Prospects for Recovery and Sustainable Development in Africa (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1996)

2 Kathryn Yusoff, “Mine as Paradigm”, 2021, in: E-Flux Architecture (accessed 17 January 2022)

3 Reginald Fenton, 1911

4 Geoffrey Wheatcroft, The Randlords (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1985)

5 Colin Newbury, “Technology, capital and consolidation: the performance of De Beers Mining Company Ltd. 1880-1889”, in: The Business History Review, issue 61, 1987

6 Anthony Trollope, South Africa Volume 1 (London: Chapman and Hill, 1878)

7 The Glen Grey Speech: A transcription of Cecil John Rhodes’ Speech on the Second Rereading of the Glen Grey Act to the Cape House Parliament on 30 July 1894, available from: https://www.sahistory.org.za/

8 Colson Whitehead,The Underground Railroad (New York: Doubleday books, 2016)

9 Ann Laura Stoler (Ed.) Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2013)

10 Gayatri Spivak, Death of a Discipline (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003)