Text | Interview | MaerzMusik 2025

An Opera of Breathing

Chaya Czernowin in conversation with Frank Madlener

Frank Madlener (FM): Can you tell us about the space that you are creating with “POETICA” – you spoke of a “memory palace” – and about the sense of cohesion you want to create in this space?

Chaya Czernowin (CC): “POETICA” is not exactly about “cohesion”. It is more like a layer, inside a layer, inside a layer ... in some kind of consciousness. Or rather, it is like a sort of terrain, which would be constituted of many layers of rocks: a topological space. What we are dealing with in “POETICA” is not actually archaeological, of course, but it is about exposing these layers. In that sense, this piece is kind of a sister-piece to “HIDDEN”, a quartet with electronics. “HIDDEN” was, in a way, comparable to going down into the depths of water, whereas “POETICA” symbolises going down into the shadows of words, into the shadows of finding meaning. It all started with the notion of memory, because memory is a very complex layered system within our consciousness. Some memories are hidden from us – traumatic memories – while others are more approachable, and some others are constantly changing, because we forget and we reshape them under the external influence of other people. Memory is something that is very fluid and not fixed. For a long time, we believed that memory is like a sort of cabinet that we physically keep locked somewhere in our brain and that we could open to access it. Of course, that is not how it works, as science has later shown. Memory is constantly active, fluid and changing.

Chaya Czernowin

FM: When you initially named your piece “Memory Palace”, you referred to how memory is closely connected to specific spaces and moves from one space to another. Are there any lyrics in “POETICA” that are anchoring this memory?

CC: There are no real lyrics, per se. The piece has more to do with the interaction between memory and the present. First, we have the soloist, Steven Schick – a genius percussionist – then the four members of the Percussions de Strasbourg who are surrounding him, and finally comes a very mysterious ensemble comprising three string instruments which are hidden, away from the stage. Although this decision was originally made due to space constraints to make the piece more functional, it eventually became one of its most interesting parts. It shows how some constraints can end up turning into the biggest asset of a piece. What I mean when I say that the trio is “hidden” is that we don’t know whether they exist at all: in fact, they are not even always there. They are forced into being through the play of the Percussions de Strasbourg.

FM: And about the electronics?

CC: We could not get the result we were looking for by only using the sound produced naturally by the strings. So, we had to tweak their sound so that it amplifies that of the percussions while also seeming like the strings were present within the percussions’ consciousness, as though they were an organic, thinking being. I am opening a kind of psychological arena, where we have the soloist, the percussions and the strings. The soloist manifests himself by his breathing. In a way, you can say that the whole piece is just like one long breath.

FM: Could we say that you are transforming the instruments into living subjectivities? At the start of the writing process, you were questioning whether your piece was an installation or a performance. Did you, in some way, end up combining both?

CC: I would say it really became a performance. But it is very elemental, using the minimum needed. Just like when we breathe, without even being aware of it. Breath is life, the whole universe itself is breathing, contracting. It is the same with “POETICA”.

FM: You have a strong background in theatre. Would you say this piece also has some kind of dramatic dimension, almost like an opera?

CC: It is very operatic indeed. You could call it the “opera of breathing”, or the “opera of the breath”.

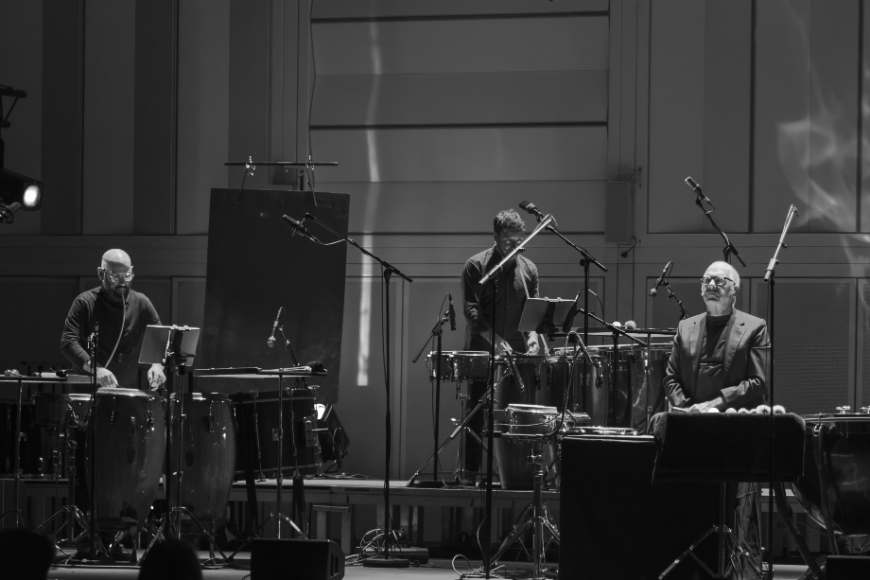

Steven Schick, POETICA by Chaya Czernowin, performance at Espace de projection, IRCAM, 2024

FM: With this piece, are you proposing a new form of communication? Not only between the sound and electronics but with the public as well?

CC: I would say it is more about a communication between the layers that constitute the piece, as we go down into consciousness. It is about connecting the different spaces within one mind. But this “opera of the breath” is also suggesting a certain objectivity, because – while this internal conversation is going on – we can also hear the sounds of demonstrations. I was there during the demonstrations that took place in Paris and Tel Aviv, and I have also been watching TV here in America. So, I decided to record them, adding some other sources as well. These recordings bring an external dimension to the piece and give the impression that the ensemble is trying to survive the burning of the world. Because, when we think about it, what are demonstrations really about? It is nothing more than a gathering of thousands of people clamouring about things they are defending or fighting against. What we hear are therefore the screams of an unhappy world, which has no control over the constant changes it is facing. And in this world which is hurting us, we have to fight to remain human. Just like we do when we are focused on our breathing – how it goes up and down, like a meditative act, in the face of a changing and treacherous world.

FM: You are creating a connection between directionality and slowness, which is a tricky topic in musical composition. How do you manage it?

CC: In the past, it was considered that the field of music was constituted of three different categories: processes, spaces and events. Now, we are realising that there is no such a dialectic division, and that these categories are more on a continuum. When we are in a space, even though it is cyclical, like breathing, there is a very slow process that is sneaking into the breathing, making it deeper, heavier. It then becomes more difficult to breathe despite the process in itself not being difficult, and it can take some time before we realise that something has changed. The speed (or here, slowness) depends on how invested we are in the space or the process. A fast-paced development brings us to the completion of the process, whereas a slow development takes us into the spatial dimension. Space is never solid, or fixed, it is always changing. What is fixed is rather the notion of time scaling, which is something very important to consider as well.

Chaya Czernowin is a composer and has been the Walter Bigelow Rosen Professor of Music at Harvard University since 2009.

Frank Madlener is a cultural manager and the director of IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique) in Paris.

The interview was conducted on the occasion of the French premiere of “POETICA” in June 2024 at ManiFeste, the multidisciplinary festival of IRCAM.