Text | Conversation | MaerzMusik 2025

Voice Is the Original Instrument

Joan La Barbara in conversation with Ute Wassermann

Ute Wassermann (UW): “Voice is the Original Instrument” is the title of both your concert and your solo album from 1976. It had a huge impression on me as a young art student the early 80s because it’s conceptual and concise and at the same time very imaginative. It is also a manifesto, right?

Joan La Barbara (JLB): It really was intended as that. I used the title of my first solo concert and then I keep using it because it still seems to be surprising to people how much the voice can do. When I went about exploring the voice, I was more or less inspired by instrumentalists exploring their instruments. I thought I should do this with the voice and just start exploring. I did all sorts of things; I started with imitating those other instruments, but I also did this sensory deprivation experiment called “Hear What I Feel”.

UW: This is a very special piece.

JLB: Obviously, it was designed to hopefully surprise a sound out of me beyond the technique, and I did this for the first time live in performance. I had a space separate from the performance space where I had taped my eyes shut with cotton balls and masking tape. I sat in this room not touching anything for an hour before the performance. I had six clear glass dishes set up on this little table. I told my assistant: “You can choose anything to put in the glass dishes. The only stipulations are that it not crawl and it not injure me.”

I was going to be vulnerable, and I don’t like bugs [laughs]. I wanted to do this in front of an audience because of the heightened state of awareness you’re in when you’re in the performance mode. I was led out by the assistant, still with my eyes taped shut, and sat at a little stool behind this table with the glass dishes, just touching the different substances. I wasn’t trying to identify anything. I wasn’t trying to do anything musical. I was just trying to give an immediate vocal response to what I was touching.

UW: So you wired a tactile experience directly to your vocal folds.

JLB: Yes, it was a fascinating experience to do live.

UW: I think the element of surprise is very important: how do I react vocally to an unforeseen situation? That’s so different from practicing a piece.

JLB: Yes. It is also very much about improvisation though. I didn’t want to make a musical statement about what I was doing. It was meant to be a kind of scientific experiment. The idea is to try to discover something new.

UW: Which is very courageous in front of an audience.

JLB: Absolutely, taking the audience with me on this journey and trusting that they would go with me, which I thought was very important.

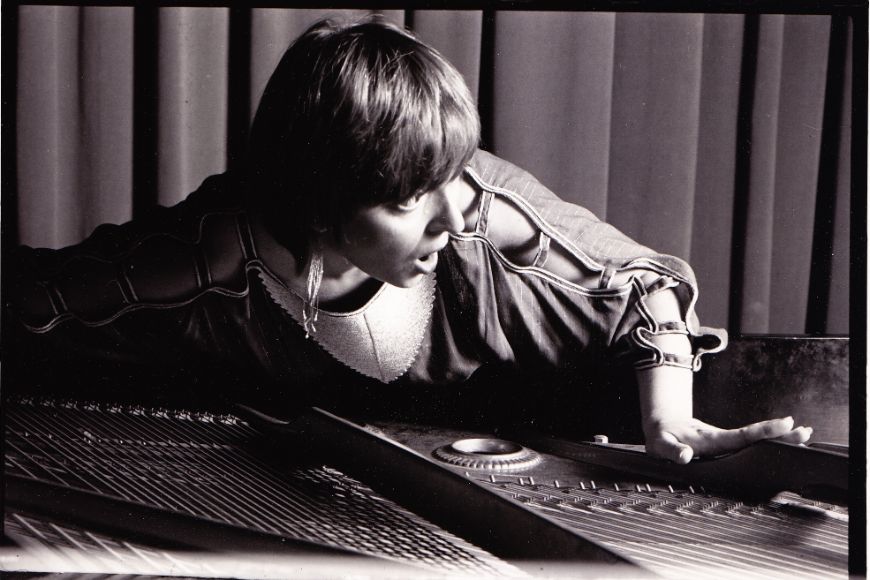

Joan La Barbara in concert in Los Angeles, 1984

UW: Some of your pieces span a long period of time. “Solitary Journeys of the Mind” spans from 2011 to now – constantly growing and evolving, just like your voice as time goes by. This notion of time is much more complex than just linear time.

JLB: There are certain vocal gestures that are part of the piece. But it’s also a piece about the transformation of these gestures in real time. It’s a “real-time” composition – which is what improvisation is – taking those decisions: do I continue? How do I allow this sound to morph into something new? If I’m making a rhythmic pattern, do I want to extend it or do I want to go to something that is smoother? Even with the pieces that have fixed backing tracks that have their own time, I can add something to it because I know what’s coming. I can introduce something that I know the audience is going to hear but hasn’t heard yet.

UW: Let’s talk about “October Music: Star Showers and Extraterrestrials”, which you describe as a “sound painting”. It is based on the contemplation of the sky with its shooting stars and sparkling clusters. Is the sky a living score and a collaborator in the sense that it ignites a compositional process?

JLB: Yes, it’s the stars that you see if you’re lucky enough – if you’re away from the light pollution of the cities, you can actually see the night sky and all the wonders that are there. But it also takes this imaginary journey into possible beings from another space. I do play around with the idea of what might be a different language, a different sound that might come out of these beings, and what kind of sounds I can emit that may surprise me still. “October Music” is this combination of sounds that I know, sounds that I imagine and then layering them up into this “sonic atmosphere”. In performance I’m working with those recorded sounds and adding yet another layer.

UW: In the case of “Erin”, too, it was an emotional experience – a reaction to a photo – that opened your imagination and gave way to a composition.

JLB: Yes, exactly. The photograph was of a father carrying the coffin of his son who had been a member of the Irish Republican Army and died in a hunger strike. I was overwhelmed by this photograph. It led me not only to that emotional reaction but also to thinking about it and imagining and considering all the incredible writers who came from Ireland; James Joyce and Samuel Beckett and many others. The people are in my imagination, they are not real in any shape or form. They are sort of alien creatures that I create sometimes. It’s about an imaginary language. In the centrepiece is this little one-syllable language that I created. I don’t know where that came from. It just happened; it was not predetermined. And I thought: that’s really interesting, I’ll let this develop. I go into this big multiphonic dirge, many layers of multiphonics and reinforced harmonics, and then come back to that made up language at the very end with this string of monosyllables that make a word or maybe a sentence.

Whether I decide to make the playing playful or more intellectual – all of that is part and parcel of being in the moment of composition in the studio. So, when I make these pieces – with certain exceptions where I have things written out ahead of time – most of the time I have gestures in mind, or I do a lot of graphics, I do a lot of just playing.

UW: How do you notate your pieces?

JLB: It’s a combination of things. If it is pitch material that I want to achieve and replicate, then I write down the pitch material. More often it’s a vocal gesture and that is rather expressed in a graphic for me. Because I see sound when I’m making it.

UW: You see the shapes?

JLB: The shapes and the sounds are occurring simultaneously. I’m experiencing the energy that it requires to make the sounds. Sometimes I come out with a sound and it’s weird, so I don’t want to go there again. I know perhaps that that sound was a one-time event and I may not be able to replicate it. I can choose then to use the energy required to make that sound and see what comes out next. It’s a very fluid process and there’s a constant sense of discovery.

UW: In “Windows ...” you are inspired by the curved shapes of architecture.

JLB: My father was in the building construction business, so he taught me drafting. He taught me how to read floor plans and design plans, things like that. I think about architecture in a certain way, the necessities of architecture and the fanciful architectural ideas that you can add to them. That’s been part and parcel of my being since I was a child. The drawing of scores to me is very much like doing an architectural plan. Generally, I record the foundation tracks first, all these layers for the foundation, so I know whether I’m dealing with microtones that create beats or whether I’m doing a more solid structure. Then I begin layering on top of that.

UW: For “Windows …” you create space with a variety of intricate layers, like the sounds of wind, almost like spider webs. You can really zoom in as a listener.

JLB: That’s what I intend. You speak about the wind; of course, it’s not the wind. It’s me creating wind. It’s very difficult to record actual wind. You need special equipment, special microphones and all of this. So actually, creating the wind by myself is easier than trying to record the wind. Those various kinds of wind sounds are all vocally produced winds using the breath and the tongue and where in the instrument you place the tongue, as well as how you move the tongue to vary your wind sounds.

UW: This is fascinating. Is there anything else you want to talk about?

JLB: Process. In my process of composing, I don’t have a system. I work from inspiration, and that inspiration, as you’ve mentioned, can come from a photograph, from moments, paintings or walking in the environment. The inspiration comes from various sources. After it’s filtered, and once I have an idea, a concept, I start a stream-of-consciousness list. I write everything down and I try not to censor. I’m trying to access what’s in my mind, what’s in my brain, which we don’t know very much about scientifically.

UW: You don’t narrow it down at an early stage, but you go through a procedure of letting things happen.

JLB: Letting things happen and discovering things. As I’m writing, I am discovering: wow, I didn’t realise I thought that. That’s part of my process. Then, I go back and I read what I have written and see where the music may be. It may take several read-throughs to discover where the music is. I also do drawings, not figurative drawings necessarily, but energy drawings. Again, I access what I’m sensing, what I’m feeling, what I’m experiencing: just letting the pen go over paper and finding out after the fact. And then, when I get more of a kernel of the ideas, then I’ll start working with the sound. I often don’t know the whole map; I start working with the sounds to see what they are – discovering the shape and the essence of the sounds as I’m making them.

Joan La Barbara is a singer as well as a composer, performer and sound artist. She uses her own experimental vocal techniques to expand the traditional boundaries of singing.

Ute Wassermann is an experimental singer, composer-performer and improviser. At the core of her research is an uncompromised exploration of the voice and its spatial extensions.