Text | Interview | Berliner Festspiele 2020

“I felt like I was riding on this material like a boat and going home”

Interview with film director Alvin Tsang

As part of our preparation for the film series “Sundays of Hong Kong”, we asked film maker Alvin Tsang for an interview. We talked about his film “Reunification” (2015), which deals with his family's emigration from Hong Kong to Los Angeles in the early 1980s. Alvin Tsang told us about the initial impulse for this project, about his working methods, his aesthetic and narrative role models and the difficult search for the conclusion of such an autobiographical project.

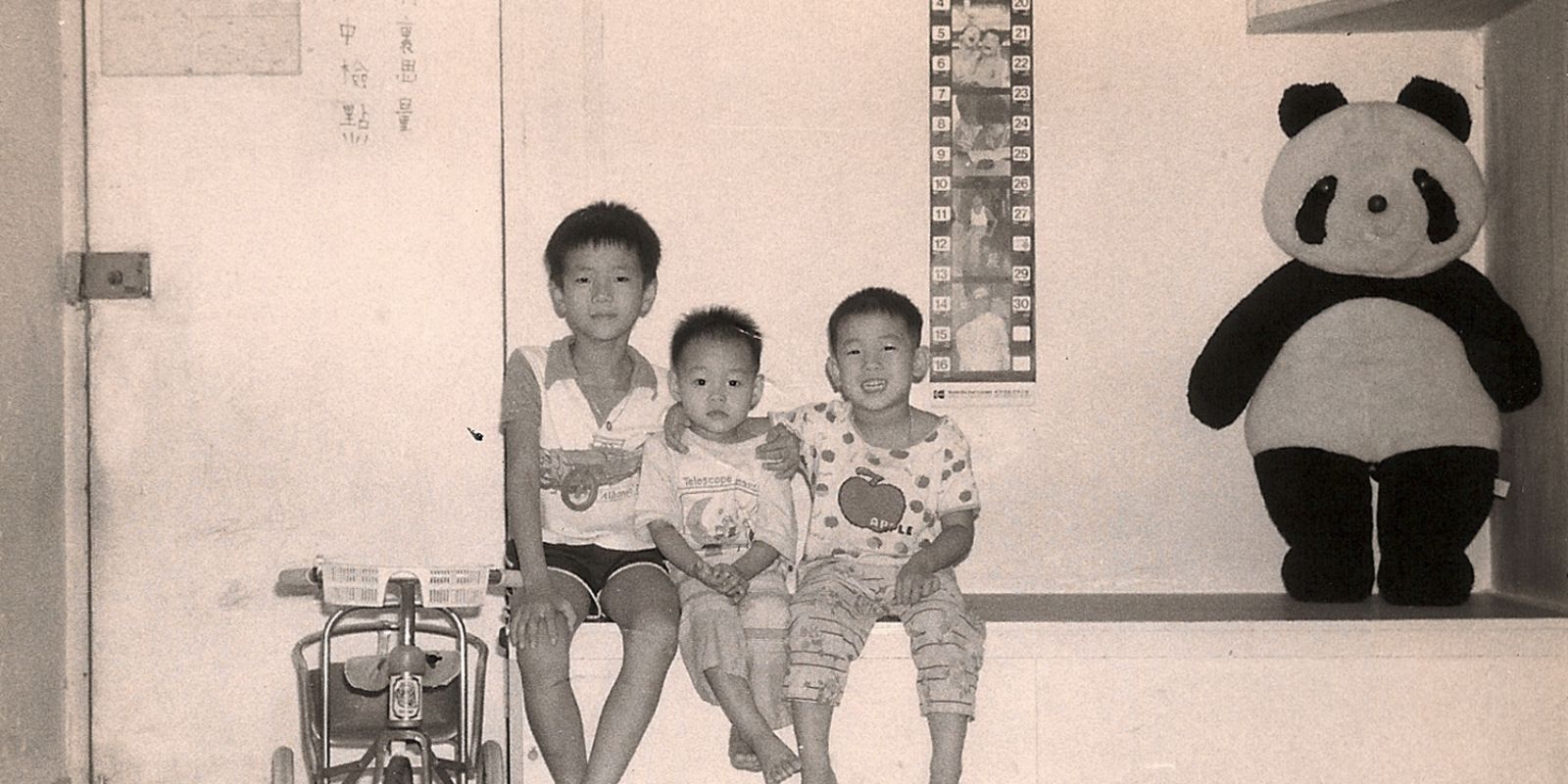

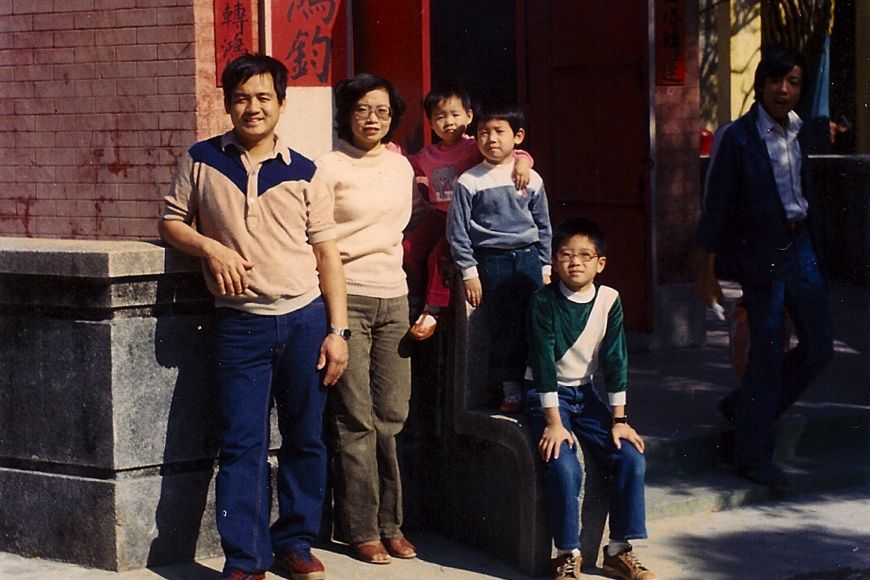

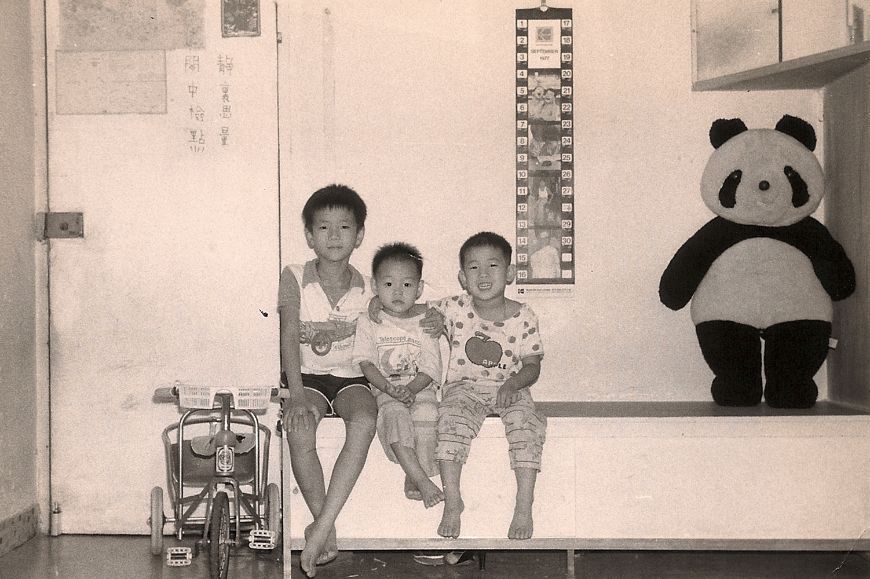

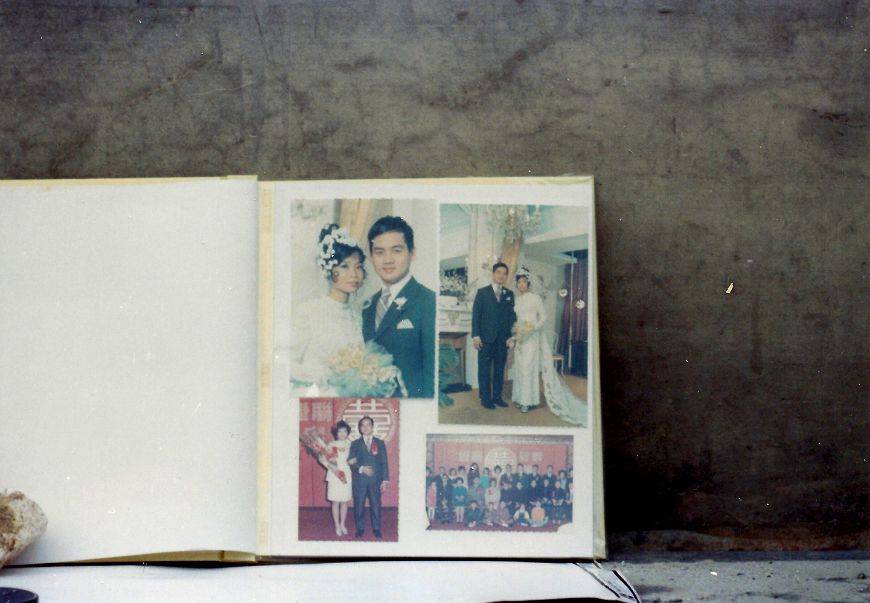

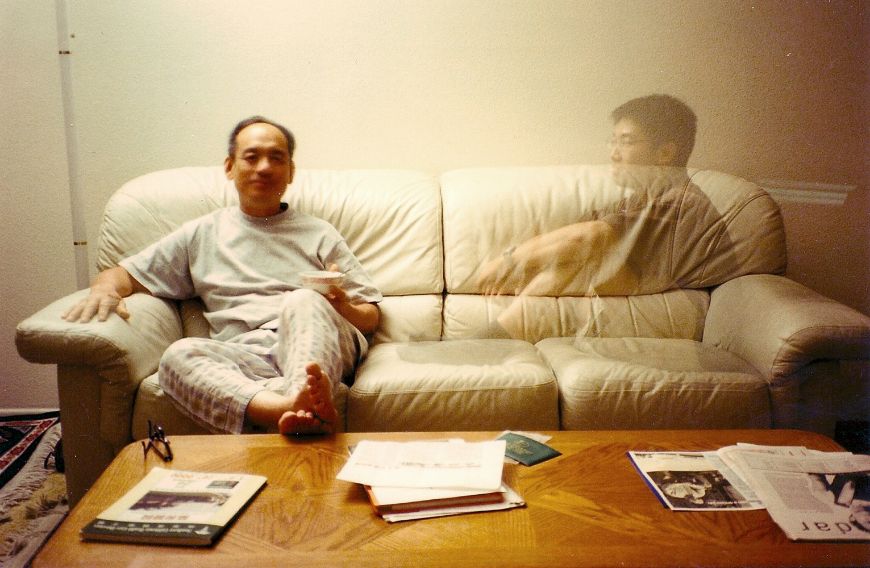

Filmstill: “Reunification”

Everyday after school, my brother, sister and I took a two-hour bus ride out to a gigantic interior design building in West Hollywood. This building housed over 500 high-end interior design showrooms, including shops for corporate office furniture, exotic Asian rugs, high-end home furniture, antique furniture, country farm-style furniture etc. My family cleaned around thirty offices. We all arrived at 5:00 pm when most of the office workers had gone home, and we began cleaning. My brother, stepfather and I threw out the trash and vacuumed, while my sister and mom (and a female cousin who was living with us at the time) washed coffee mugs and pots, and dusted and wiped down tables and glass doors. Sometimes while cleaning, a worker or two would still be working at their desks and I had to shyly ask them if I can take their trash cans. I felt a sense of inferiority when I saw them and I was very shy when they tried to talk to me. They were well-dressed in office clothing and I had to throw out their trash. It was embarrassing. I had internalised this feeling and had to deal with it many years later. We cleaned until around 8:00 pm before the drive home. Then my mom cooked dinner while we started our homework. After dinner, we didn’t go to bed until we finished our homework, which was usually around 11:00 or midnight.

Why couldn't your parents protect you from this hard work?My father, mother and stepfather weren’t highly educated – my mom went to high school while my stepfather and father never finished middle school. But they did their best to keep the family afloat. My parents decided that the three of us children should live with my mom and stepfather since they could double the effort in supporting us. So my dad lived by himself frugally and worked several low-wage jobs (and would one day help us pay off our student loans and buy us each a car with his savings after college). My mom and stepfather also worked during the day but their wages just weren’t enough to support us. So my stepfather connected us with the showrooms and we got more and more business. We children had to chip in our efforts to help the family survive. Working was also a way for my mom and stepfather to protect us from hanging out with the wrong crowd after school. Each of us spent about 10 years cleaning until we each turned 18 and left for college. My sister and brother never went back to that building. For me, sometimes when I fly back from NYC (where I have lived since I turned 30) to Los Angeles to visit, my mom and stepfather would pick me up from the airport and go there directly to finish cleaning a couple of showrooms, which are all they have left nowadays. While they clean, I would walk around and feel nostalgic. The cleaning scene in the film was one of those times when I’d just arrived from the airport.

Filmstill: “Reunification”

I didn’t have much of an interest academically. Being from Hong Kong, I kept up with mainstream Hong Kong films while growing up. In high school, I loved John Woo’s films and Stephen Chow’s comedies. I took a couple of black and white film photography classes and a TV production class which I really enjoyed. So I decided to study filmmaking and went to University of California, San Diego. I majored in Visual Arts with an emphasis on video and film. What a whole new world that opened up for me and how my taste in cinema had changed since! I didn’t know that you can look at film as a poetic art form. Through French New Wave professors like Babette Mangolte (cinematographer for Chantal Akerman) and Jean-Pierre Gorin (co-director of “Tout va Bien” with Jean-Luc Godard, 1972), I was exposed to silent, European and Japanese cinema. I also got exposed to American video art and experimental cinema. It was really challenging to soak it all in and I fell asleep through so many silent films, but it changed me through time. It taught me the many different ways moving images can be created, and that the moving image can be a meditative experience. Iranian films by Majid Majidi and Abbas Kiarostami really gave me a deep sense of the purity of children and their world. I started to get really in tune with narrations and how simplicity and directness is best for poetry in film. Narration writing from Robert Bresson, Agnes Varda and Wong Kar Wai really inspired me. I never read much while growing up, but watching their films was like reading literature for me. In the mid-90s, I remember watching “Happy Together” (1997) and “Ashes of Time” (1994). Christopher Doyle’s dynamic handheld cinematography, William Chang’s editing, and Wong Kar Wai’s narration in Cantonese, my native tongue, got me hooked and I said to myself, “I really love that dark mood, and I want to make something now.” Digital video and non-linear editing also came during that time and it was a very exciting time for filmmaking. Many people aspired to shooting handheld. I bought a Digital8 tape camcorder after I graduated and started playing with it, shooting everything in life that interested me, capturing my friends, my family, interesting places and spaces. I just wanted to experiment and exercise camera techniques. I digitised the footage, edited many scenes and through time, they collected. I didn’t have a particular film in mind while doing it. But little did I know, this wandering collection of footage was the beginning of “Reunification”, for the next 17 years.

Sie müssen Drittanbieter-Cookies aktivieren, um diesen Inhalt anzuzeigen.

Trailer: “Reunification” © Alvin Tsang

So did you find your narrative through screening your filmographic archive? Can you describe further intrinsic motivations for “Reunification”?I was 22 years old and had just graduated from college. Bouts of depression and anxiety suddenly crept up from my unconscious and overwhelmed me. I felt lost. Journaling was my way of expressing these feelings in the rawest form. When I wasn’t feeling sad, I began writing narrations in my journal for the many scenes that I had already edited. I put together a collection of many edited scenes and let a few of my close friends watch them. They told me that there was a storyline about my family that really stuck out while watching it. So with that in mind, I started going in that direction more and more through each cut. I realised my motivation very slowly – to understand my family and my place in it. I wanted to understand why I was feeling so much sadness in life. Why I wasn’t happier, like my friends? Why is my family so divided? Why did my parents have to get divorced? Why did we have to work so damn hard while growing up? Why did we move to the US? Why was I the one to be left behind in Hong Kong while my mom and siblings came over first? I needed to understand it all for myself.

Your film begins with the story of a typhoon that hit Hong Kong one night. I have the feeling that it is paradigmatic for everything that happens afterwards. Can you please tell us this story again?You are right. I was six years old then. This memory of the typhoon happening while all five of us were sitting together in bed was the height of our family unity. We lived on the 12th floor of a government housing complex in Hong Kong where the windows were made from hard plastic sheets. On that night, the thunder and wind were powerful and scary, and the rain was hitting hard on the plastic. Despite that, I felt such feelings of security and warmth because the whole family of five were together on our wooden bed, lit by candlelight. I remember my parents and older brother were joking around to lighten the mood, while my sister and I were playfully biting each other’s back and laughing. While writing about this memory in my journal, a lightbulb flashed in my mind with the thought that this is the perfect beginning for the film!

Filmstill: “Reunification”

I really appreciate your characterisation of it as being a “triple burden” and yes, you really hit it right on the mark there about the film being a testament to healing from loss and finding faith. I would like it to be seen in that redemptive light. It tells me that I have done something right.

One part of the story is the communication meltdown between your parents and you children. How did you manage to find the right narrative and form of story-telling for the absent?Our relationship with David, our stepdad, wasn’t good. This had made our relation with our mom suffer as well. We kids grew up thinking that the divorce meant that David, our enemy, stole our mom from our dad. We had many fights with him while growing up and as a result, my mom and we just got more and more distant. We haven’t really had a chance to re-examine this view. For me, I realised that I needed to find a way to look deeper and to really examine her relationship with my dad. Maybe it has nothing to do with David. I’m now independent on my own, and I wanted to make peace with her. I wanted to hear it from her own mouth. So I decided to turn on the camera to ask her about the divorce. I knew that she would become defensive before I asked her, but I felt that sometimes there was just no better time than now. As expected, she refused to answer. I decided to not respond and let her talk, while the camera continued to record. How she refused to answer was so much more revealing for the film.

How did your living environment affect your perspective and your working methods?Living in New York really allowed me to see things from an “outsider” perspective. Since I was only able to go back to Los Angeles a couple of times a year, the visits were kind of a “catch up” on what was happening in LA while I was gone. When I went back to LA I became more of an active investigator. Before moving to NYC, the footage was a passive wandering of sorts, which didn’t allow the film to take off. I was physically too close to the family. But this time, I became more active and filmed my mom’s interview, my sister’s interview, and footage of the inside of my parents' house when they weren’t there. Even my parents’ houseplants and the photos that they kept around the house gave personality to who they are and took on a sense of intrigue. It was scary to confront my mom but it was also exciting. I told myself that as long as I approach it as objectively as I can and to come from a place of empathy without creating unnecessary drama, everything will be ok. I trusted that it wouldn't become mere reality TV that cheapens life, which I feared most. And it didn’t. This footage activated the film and became the main material for the second act.

Filmstill: “Reunification”

I edited an imaginary scene of my mom and dad being together in it (they haven't seen each other since 1985) by juxtaposing individual footage of each of them playing with my niece at my brother’s house at different times. I really liked this scene, but I wasn’t fully happy with it as being the film’s ending since it was not reality but a fantasy. So I just let it sit there once again for a while. But how life surprised me so gloriously! Not long after that, my sister and her then-fiancé announced that they will be getting married not in LA, but in Hong Kong. Of course I had to bring my camera there to make a wedding video for them. So my mom went, and of course I had to film her. My dad arrived in Hong Kong several days later to celebrate, and of course I had to film him as well. I captured all of the family functions when everyone was so happy together and the sense of family unity was so intense. I savoured every moment of the trip, tape after tape. My hunger was so strong for this sense of family unity. Before returning to the US, my sister and I decided to go back to the neighbourhood where we grew up, and I naturally brought my camera. This Hong Kong footage became the perfect closure that tied everything together. The editing from that point on became so effortless and fun to work with. My journaling became much more reflective and constructive. The edited footage aroused such direct reflections that whatever I wrote down became much of the narration without much change. It felt like I was riding on this material like a boat and “going home.”

Were you in an exchange with your family about working on the film? How much interest in reflecting on the past did your family show? And weren’t you afraid that the film might go beyond the boundaries of what you and your family wanted to make public?Neither my mom nor my dad knew that I was making a film when I interviewed them. I told them that I just wanted to record them for myself to keep. My dad has always been open to being on camera. As for my mom, she cautiously answered my questions about us growing up at her house. But when I asked her about the divorce with my dad, she broke down and refused to answer. As mentioned in the film, the person who helped me see my mom’s perspective was my sister, Mimi. I went down to San Diego, where Mimi lives, to show her some of the interview footage. We agreed that the only thing we can really do now is for Mimi to put herself in my mom’s shoes and speak on camera as a woman in her 30s who was alone with two kids in America and without a husband. We took an empathetic stance. She gave a really good female perspective.

While making the film, I had tremendous fears and doubts about showing it to the public one day. I often discouraged myself with the disapproving and judgmental voices within – “no one in America would care about an Asian family like mine,” or “well, isn’t this a narcissistic piece?” But I refused to give up because I knew for a fact that I won’t have peace until I had finished it. I’m so grateful for those friends and older mentors who kept me honest by encouraging and reassuring me that those self-doubts are not true, and that I must fight them. By the time I finished the film, I was no longer afraid to expose my family story because I have already dealt with it while making it, and I know that the last act of the film really brought the film full circle. Whenever the audience asks me about my thoughts on exposing my family story to the public, I would admit that this film is my selfish act to gain peace for myself and I had to do it, but I did it with as much care as possible.

Filmstill: “Reunification”

This film required this long simmering length of time to be completed because one had to simultaneously live life and process everyday emotions, remember the past through journaling about it, and create something that mirrors life as much as possible through an artistic medium. This process must go from life to art and back, over and over again, until they become in sync.

For me, the film is not just so great because of its story and its unadorned way of recreating it. A perhaps not insignificant aspect for me is the language of sound and the language of images: the voice over, the rhythm, the tempo and the music you used, but also the photographic quality of the images and the different principles of montage and double exposures. Can you tell us a bit about the aesthetics of the film?The goal of this film was to activate memories, to make them as real as possible, and to give order to them. I wanted the form of this film to go beyond a standard documentary and be more and more cinematic as I was making it. Since this is an exploratory film from the ground up, the methods of creating each scene must also be exploratory and open in order to express the layered and complex feelings of different memories. There were a lot of visual treatments in terms of speed, double exposures and montages to probe into dreams (and nightmares) and fantasies. I did my best to ground them to the memories so they don’t just become editing tricks. For my use of photos, I wanted to keep the gaze on each photograph for a while to really let them sink in and become part of the experience. The ambient sounds make the characters in these photos come even more alive, as if moving in the photos. I was trying to be aware of the rhythm and pacing as much as possible, making a calm film out of what seemed like a complete chaos. Through each edit, I tailored the narration to become more and more simple and direct, and paced it more rhythmically together with the image and sound. I really admire how Robert Bresson does this through his films.

The film's music is very impressive. Can you tell us about it?Joana Karselis, the music composer (from the UK), generously gave me her all in creating the wonderful soundtrack. I gave her as many notes as I could on my feelings for each scene and the scenes where I felt music was needed. Her eclectic repertoire in classical, electronic and their mixture really impress me. The music complements the film really well in the simplicity and directness of its mood. For my sister’s wedding scene, I gave her a prerecorded track of a traditional Chinese ballad played on the erhu that I recorded on the subway platform, and she recreated it with Western strings. She respected the film’s human story and characters and didn’t orientalise the soundtrack in anyway.

Filmstill: “Reunification”

I went to Hong Kong last summer (2019) when the protests were happening. Before that, I premiered the film there in 2016 at the Hong Kong Independent Film Festival and met many wonderful friends. I was only able to see them briefly in July 2019, and wish I had had more time with them. Talking with artist friends and many working folks like taxi drivers and local shop workers gave me perspective on what the local working man is going through. It makes me feel very concerned for Hong Kong residents. The government is not on their side and yet it wants them to be nationalistic towards communism. Where’s the incentive in that? Where is their opportunity for growth? If there is economic progress, then for whom? House prices are up the roof and the most expensive in the world. Job opportunities are scarce. The city is so physically compressed with very little room to grow for the poor. Some live in cages like animals! The young people, many of them very educated and intelligent, have to stay cooped up in tiny confined spaces with their families, with very little future to start a family and become more independent. The government is squeezing their livelihoods. I applaud the youths for being so creative in expressing their feelings in different ways. When they express their pains, the government becomes brutal, humiliates them and tries to crush them at every turn. When some of them feel desperate and fight back, the government now brands the whole dissenting movement as violent. Hong Kongers are a very tolerant and thoughtful people who deserve respect from the government. Though the path looks bleaker and bleaker going forward towards 2046, focused creativity is the torch that maintains a clear vision on this dark path. The common man needs help now. Let him and her flourish!

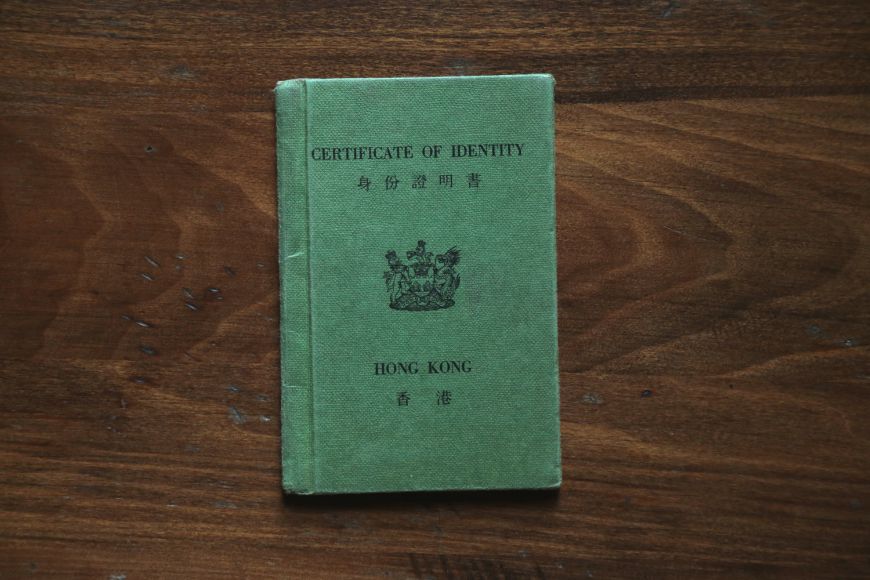

Perhaps you can elaborate a little about your current work?I’m currently working on an offshoot piece from “Reunification” entitled “When Home is Elsewhere.” This short documentary explores the idea of home, the feeling of home, and the anxiety of not having “found home” by focusing on my father’s life path. My father is a frugal and practical man. At 74 years old, his apartment is empty – no bed, no sofa, only a makeshift table small enough for one person to eat on. Any sound that one makes creates echoes. When I asked him why he doesn't make his home more comfortable, he said, “This is not my home. I may move somewhere else tomorrow.” His response reminds me of a nomad, a homeless person, someone who is ready to flee on short notice – a refugee. His home has always been materially scanty. But this echo is just unbearable! In this film, I want to understand what he is looking for and why he is always ready to leave to go elsewhere. I want to know how his experiences – as an orphan, a teenage-refugee from Vietnam to Hong Kong, an immigrant, a divorcee, a father – have shaped him and whether historical events have greater power than I could ever realise.

Filmstill: “When Home is Elsewhere”

I want to thank you for this interview, and I want to thank Berliner Festspiele and Gropius Bau for this opportunity to share the film in Berlin. Stay safe and healthy during this time!

Thank you, Alvin Tsang!The film “Reunification” by Alvin Tsang is available as part of our online film series “Sundays for Hong Kong II” on our website from 9 April, 16:00 – 7 May 2020, 15:59.